Gaming altmetrics

Many people looking at altmetrics use a lot of social media data and there are well-established spammy industries built up around paying for tweets and Facebook Likes. Given that we know a small minority of researchers already resort to manipulating citations, it’s not much of a leap to wonder whether or not an unscrupulous author might spend $100 to try and raise the profile of one of their papers without having to do any, you know, work. How much of this goes on? How can we spot it? What should our reaction be?

We were one of the original signers of DORA, the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment. One thing that it commits us to is clarity around gaming (the ‘exploiting the system’ kind rather than the GTA V kind):

13. Be clear that inappropriate manipulation of metrics will not be tolerated; be explicit about what constitutes inappropriate manipulation and what measures will be taken to combat this.

I’ve been looking at our policies and systems around this recently. Identifying what is and isn’t acceptable is not necessarily as simple as you might think, which is best illustrated by example:

- Alice has a new paper out. She tweets about it, and twenty of her (non-academic) friends retweet her in support.

Is that gaming? Remember that the Altmetric score measures attention, not quality. How about these?

- Alice has a new paper out. She tweets about it. HootSuite automatically posts all of her tweets to Facebook and Google+.

- Alice has a new paper out. She writes about it on her lab’s blog and sends an email highlighting it to a colleague who reviews for Faculty of 1000.

- Alice has a new paper out. She asks her colleagues to share it via social media if they think it’d be useful to others.

- Alice has a new paper out. She asks those grad students of hers who blog to write about it.

- Alice has a new paper out. She believes that it contains important information for diabetes patients and so pays for an in-stream advert on Twitter.

- Alice has a new paper out. She believes that it contains important information for diabetes patients and so signs up to a ‘100 retweets for $$$’ service.

What if it wasn’t Alice, but Bob who thinks that Alice’s paper is amazing and wants the world to know? Where should you draw the line between marketing and spam? Where can you draw the line as, realistically, policing paper mentions is a Sisyphean task?

We’re very interested in what the wider community thinks. For the record: right now for us the last scenario above is unacceptable, but the others are OK to varying degrees. Again, remember that the metric we provide measures attention.

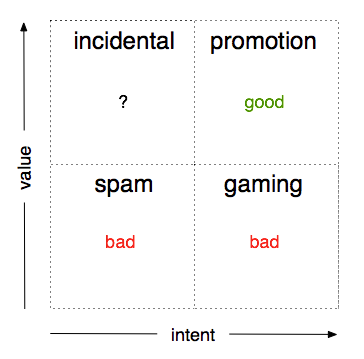

In our experience, gaming is actually pretty rare – probably because the reasons to game are, too. Nobody is getting tenure from raw tweet counts and rightly so. There are other things that can mess up an attention score though. You can imagine four fuzzy classes of activity (see the diagram below) defined by two variables: the intent to manipulate and the value added to the discussion around each article.

Not all of these classes are bad, and some pop up far more frequently than others. In brief:

Legitimate Promotion (intent exists, value added)

“Alice has a new paper out. She asks those grad students of hers who blog to write about it.”

Is the scenario outlined above acceptable? On the one hand, Alice is plainly trying to manipulate the system (not very efficiently, as pay-per-link services are even cheaper than grad students). On the other hand, ethics aside, a bunch of grad students read her work and then wrote about it somewhere that other people might see it.

This is an edge case, but in general: if there are real people behind the mentions, you’re getting legitimate-looking attention from real people, and you’re contributing at least something to the discussion around the paper, then it’s all good as far as we’re concerned.

We’d suggest to anybody pushing right up against the line that, as with content online in general, the best way to get the right people to talk about your work is to do good work. If you suspect that you might be erring on the side of spam then you probably are.

Spam (no intent, no value)

Spam networks pick up legitimate posts at random from others and replicate them, hoping to fool content-based analysis systems into thinking that they are real users. This is by far the most common scenario we see.

As you might expect, we try to pick up on spam accounts and ignore them in the Altmetric score.

Gaming (intent exists, no value)

“Alice has a new paper out. She believes that it contains important information for diabetes patients and so signs up to a ‘100 retweets for $$$’ service.”

Using pay-for-links or likes services, setting up sock puppet Twitter accounts, and creating fake blogs are all big red flags for us.

We define gaming as any activity intended to influence article metrics, where the content adds no value to the conversation around a paper and is just there to bump up numbers. If you are tweeting through a spambot to a network of spambots, then you are not adding any value to anything.

We penalise Altmetric scores heavily when we see evidence of gaming, and may pass information back to the publisher if they’ve asked us to. I don’t see any good in public shaming – putting a big red mark on the details page, for example – not least because there’s always the chance that the author wasn’t involved, but perhaps there’ll end up being a case for this.

Incidental (no intent, value but not directly related to the article)

“Just tried to access paper x but hit the paywall. Retweet if you hate all paywalls!”

Something may be legitimately promoted (or spammy) and include a link to an article – but without any intent to influence metrics systems.

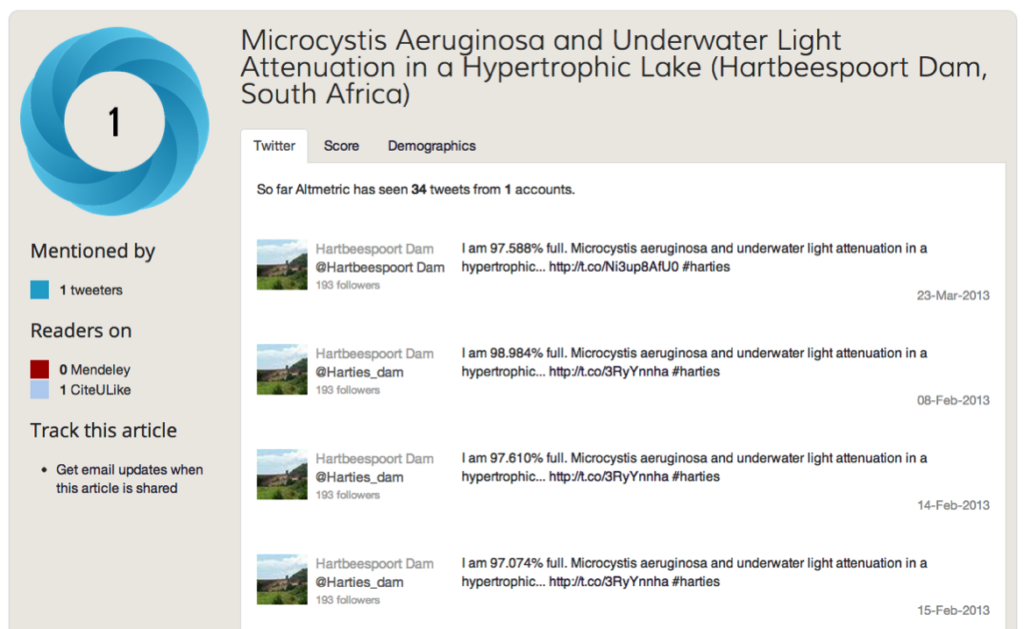

There’s the case of the auto-tweeting dam, for example:

This is a Twitter bot set up to tweet the water level in a reservoir in South Africa. Each time it does, so it includes a link to a relevant paper.

Spotting suspicious activity

Each altmetrics tool will have its own way of handling suspicious activity. We use a combination of automatic systems and manual curation, which works out well for us partly because we do three things a little bit differently:

1) We only use data sources we can audit – with one exception, each individual number we collect has metadata that we can use to investigate whether or not it’s legitimate.

This is why we don’t use Facebook Likes (you can’t see who left them or when). The one exception mentioned above is Mendeley: we can’t identify individual users on that system, but it’s a good data source so we display the reader counts anyway. Mendeley reader counts don’t influence Altmetric scores.

2) We manually curate the blogs and news sources we track – the downside here is that we have to spend a lot of time and effort on maintaining our index, but we do a great job of this. It’s why we encourage you to write in and tell us about anything we’ve missed.

3) We have enough data to have learned how to spot unusual patterns of activity – we’ve processed ~ 1.5M papers to date, and now we have a pretty good idea of what organic vs artificial patterns of attention look like. We flag up papers this way and then rely on manual curation (nothing beats eyeballing the data) to work out exactly what, if anything, is going on.

That’s not to say we pick up everything, because I’m sure we don’t. Ultimately we rely on the underlying data being visible to our customers and their users so that they can come to their own conclusion if anything looks suspect.

We’re still finding our way – come talk to us if you’ve got any ideas

We’ve got some systems and policies that work for us now, but gaming is an area where we’re very happy to work with the broader altmetrics community. If you’re interested in stuff like this, you should consider coming along to events like the PLOS ALM workshop in October – or just send us an email at [email protected] to chat.

One thing I’ve been wondering recently is if we should upload all of the data around papers that we identify as potentially being gamed to somewhere central to create a resource for people interested in automatically detecting this kind of activity. The downside is that it makes our suspicions public. What if we’re wrong or don’t have the whole story, and negatively impact somebody’s career?

Another point to think about is whether or not we should remove metrics completely from articles flagged as suspicious, or just ensure that their scores only reflect legitimate activity. Could you game your competitor’s paper to have it removed and make your own work look better as a result?

Finally (HT Alf Eaton): how transparent should we be about exactly how we spot suspicious activity? Perhaps if you spam on a Friday afternoon, or across multiple sites you’ve got a higher chance of getting past our system (or perhaps not…. ;)). In theory we like the idea that security through obscurity is a bad idea and that being open about potential weaknesses is a good incentive for us and others to then fix them. The downside is that realistically we’re a very small team and we might not be able to keep up.

Register here to receive the latest news and updates from Altmetric