How long does LEGO last in the ocean?

Every year, between 4.8 and 12.7 million metric tons of plastic end up in the ocean. Most of the research and interventions focus on the plastic that floats at or near the surface. But what about the denser items that sink to the bottom?

Surprisingly, LEGO is one of the items often found piling up on the seabed. It can get caught up in fishing nets or washed up on the shore after storms, which is how a team of researchers in the UK ended up studying it.

Read the study: “Weathering and persistence of plastic in the marine environment: Lessons from LEGO”

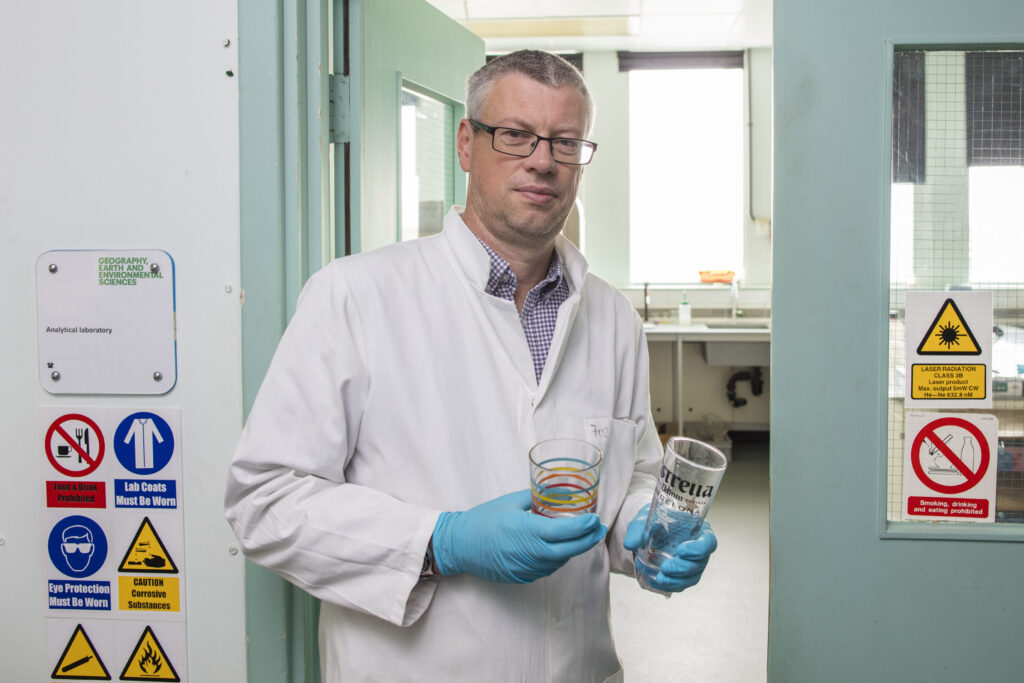

In a paper in Environmental Pollution, Dr. Andrew Turner and colleagues at the University of Plymouth describe their analysis of LEGO bricks from the ocean. Dr. Turner said:

“The study was rather unusual, because we hadn’t planned it. A colleague of mine, who is also a beach cleaner, introduced me to some of the LEGO that he’d found. I thought we could try to match the blocks with the ones we were already studying and date them.”

Dr. Turner had already been studying LEGO as a toy – specifically showing that some of the pigments used in the past had been quite harmful. As a result, he had access to data about LEGO from people’s collections, which he could use as a comparison for the bricks that had been in the sea.

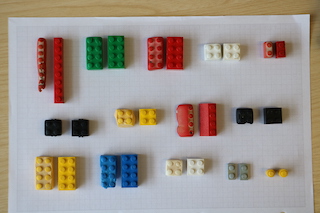

These items are ideal for studying the persistence of plastic in marine environments for a few reasons: LEGO bricks are relatively easy to date, because of the different pigments used over time and the batch markings. They are also unique in their long-term use as toys.

“Lego is an iconic kind of plastic,” Dr. Turner said. “It’s identifiable, and it has stood the test of time. I can’t think of any other plastic products that are still in use and popular 70 years later.”

Estimating the lifespan of LEGO in the ocean

One question you may be asking is how does all this LEGO end up at the bottom of the ocean? Believe it or not, the leading theory is that it is flushed down the toilet by mischievous children. Dr. Turner was skeptical at first, but research published by an insurance company showed that one of the major routes by which toys are lost is flushing – and it is estimated that millions of toys are lost this way every year.

“I can’t recall doing that myself,” Dr. Turner said, “but you can’t imagine children with LEGO sets leaving much on the beach. We’re talking about a range of blocks from over the years – it seems that flushing is the main route by which they enter the oceans, as bizarre as that sounds.”

The first challenge in studying ocean-dwelling LEGO is getting hold of it: collecting items nestled on the seabed is harder than picking up those at the surface. The LEGO bricks the team collected had been caught in fishing nets or washed up during storms. They showed clear signs of having been in the ocean: they were cracked or broken, and many had things growing on them.

But compared with floating plastic items, they showed less degradation. This is because plastic degrades by exposure to sunlight as well as mechanical abrasion. The plastic that lasts longer tends to be the denser plastic that sinks to the seabed and away from sunlight.

With LEGO bricks from the ocean, Dr. Turner and the team could start tackling the second challenge: working out when they had been manufactured and how long they had been in the ocean.

This is where the unique properties of LEGO came in useful. Bricks have batch numbers, and the pigments used have changed over time. They could compare the bricks visually with those in people’s collections to see if they looked the same, then check the batch numbers and finally analyze the pigments with a spectrometer to get a good estimate of the manufacturing date.

Since Dr. Turner had already been studying pigments, he had plenty of data for comparison. For example, when they found the red pigment cadmium sulphoselenide, they knew the brick was manufactured between the early 1970s and the early 1980s, when that pigment was being used.

With an estimate of the age of the bricks, the team could determine how long the bricks could survive at sea. Knowing how much each item would have weighed new, they could measure how much mass it had lost while in the ocean, and then estimate how long it might last in that environment.

Building public interest

The survival time the team estimated in their paper was 100–1300 years. The uncertainty in the estimate is a result of the different conditions the LEGO bricks are subjected to in the ocean, as Dr. Turner explained:

“Some LEGO may have been exposed to more sandblasting or burial; others may have been exposed to occasional beaching, or they may have been deposited in slightly shallower water where they were exposed to sunlight. And some pigments will perhaps make LEGO longer lasting than others.”

The estimate attracted the attention of the world’s news media, generating headlines announcing that LEGO will survive more than 1,000 years and resulting in an Altmetric attention score of more than 500. According to Dr. Turner, the interest is related to LEGO’s iconic status and familiarity.

“It’s something everyone can relate to,” he said. “It’s got a relationship with childhood as well – most people played with LEGO sets as children.”

Discover the coverage: https://www.altmetric.com/details/77307410

The attention was kicked off by a press release that the University of Plymouth’s news team issued, as well as coauthors sharing the article on social media. It wasn’t just the news media that responded: members of the public and other researchers have written to the team with questions and requests, including for samples of the bricks to analyze or show in meetings and talks. And an educational authority in the Netherlands contacted Dr. Turner to ask if they could use the study in an exam question.

“The study has had some wide interest in other areas as well as the media. It’s gathered quite a lot of interest, which has meant our work has had some good publicity.”

One critical aspect of the work plays into its popularity, and that’s the involvement of expert members of the public. “Perhaps some of the most innovative research comes from not planning things but from having these sparks of ideas from people. In this case, we had a background knowledge of LEGO and everything fell into place. It’s not often you have ideas that come to fruition like that.”

Dr. Turner’s top tip for promoting research

“We’ve had several research projects over the past three or four years, and the ones that have been picked up by the public the most are the ones that have involved citizen science. I think scientists quite often live in their own bubble and communicate with each other, but there’s a lot to learn from members of the public with expertise. If you are somebody who is passionate about plastic litter, if you have some interesting ideas or interesting observations, get in touch with scientists. Maybe that could lead to a small project that could widen the awareness of it and put it in a scientific context.”

Listen to the accompanying podcast episode here.

Register here to receive the latest news and updates from Altmetric